Crafting document-based apps in SwiftUI

Understand document-based apps with SwiftUI.

identified by Uniform Type Identifiers, which we Document-based apps are at the core of the Apple ecosystem. From TextEdit and Preview on macOS to creative and productivity tools on iPad and iPhone, the underlying idea is consistent: users work with files they own, stored where they choose, and open and edit them using system-provided workflows.

SwiftUI offers a modern, declarative way to build these apps through DocumentGroup, Uniform Type Identifiers, and a small set of focused protocols. In this article, we explore what a document-based app really is, how SwiftUI models documents at an architectural level, and how file types are declared and integrated with the system across platforms.

What is a Document-Based app?

In a document-based app, the primary unit of user data is an explicit file. Users intentionally create documents, open them later, edit them over time, and expect them to behave as expected at the system level. They can be moved, duplicated, renamed, shared, versioned, and backed up independently of the app that created them.

This model is fundamentally different from apps that manage all data internally, such as note-taking apps backed by databases or cloud-only storage, and from apps that let you import files and read them. In a document-based app, the file itself is the source of truth; it exists independently of your app, which serves as a tool for working with it.

By adopting this model, your app automatically integrates with the Files app on iOS and iPadOS, with Finder and standard document menus on macOS, and with system features such as drag-and-drop, document pickers, multi-window support, and file providers such as iCloud Drive. SwiftUI’s DocumentGroup is the mechanism that connects your app to all of this infrastructure.

DocumentGroup: A Document-Based App main gear

In SwiftUI, a document-based app is declared using DocumentGroup, which is a scene type.

At runtime, DocumentGroup connects your app to the system document browser, manages document lifecycles, and creates one scene or window per open document. While the visual presentation differs across platforms, the underlying behaviour remains consistent.

A minimal declaration looks like this:

@main

struct MyApp: App {

var body: some Scene {

DocumentGroup(newDocument: MyDocument()) { file in

EditorView(document: file.$document)

}

}

}

With this single scene, iOS and iPadOS present a document browser automatically, macOS enables standard document menus and windowing behaviour, and each open document is managed independently. The closure receives a FileDocumentConfiguration, which provides access to the document itself and to the file-related context.

SwiftUI also provides DocumentGroup(viewing: Document.Type) for read-only scenarios, where the app can display documents without modifying them or creating new ones.

Implementing the Document Model

Once the DocumentGroup is declared, the next step is defining what a document actually is in SwiftUI. This responsibility is handled by two closely related protocols: FileDocument and ReferenceFileDocument. Both integrate with DocumentGroup, but they encourage different architectural choices.

FileDocument

FileDocument is the most commonly used protocol and the best starting point for most apps. It is designed around value semantics and works well when a document can be represented as a struct whose entire contents are loaded and saved at once.

At this level, a document already declares which kinds of files it can read and write. Those file types are identified by Uniform Type Identifiers, which we define more explicitly in the next section.

A FileDocument must declare the UTTypes it can read, provide an initializer that reads from disk, and implement a method that writes the document back to disk. These requirements make the data flow explicit and predictable.

import SwiftUI

import UniformTypeIdentifiers

struct MyDocument: FileDocument {

static var readableContentTypes: [UTType] {

[.myAppDocument]

}

var text: String

init(text: String = "") {

self.text = text

}

init(configuration: ReadConfiguration) throws {

guard let data = configuration.file.regularFileContents,

let text = String(data: data, encoding: .utf8) else {

throw CocoaError(.fileReadCorruptFile)

}

self.text = text

}

func fileWrapper(configuration: WriteConfiguration) throws -> FileWrapper {

let data = Data(self.text.utf8)

return FileWrapper(regularFileWithContents: data)

}

}

This example uses a simple UTF-8 text representation, but the same structure applies to JSON, binary formats, or more complex encodings. SwiftUI takes care of calling these methods at the appropriate times when documents are opened, saved, or duplicated.

ReferenceFileDocument

ReferenceFileDocument exists for cases where value semantics are not sufficient. It is intended for document models that are classes, where identity matters and where the document may be mutated incrementally over time.

This protocol introduces snapshot-based saving and more advanced lifecycle hooks. It is useful for large documents, complex object graphs, or integrations with existing persistence systems. At the same time, it is more complex to implement correctly and easier to misuse.

For many apps, especially those new to document-based architectures, FileDocument remains the better choice. ReferenceFileDocument should be adopted intentionally, only if necessary.

Defining UTTypes in Code

With the document model in place, we can now look at how file types are represented in code. Swift uses the UniformTypeIdentifiers framework to provide a type-safe API around UTTypes.

Rather than scattering string identifiers throughout your app, the recommended approach is to define extensions on UTType.

import UniformTypeIdentifiers

extension UTType {

static let myAppDocument = UTType(exportedAs: "com.example.myapp.document")

}

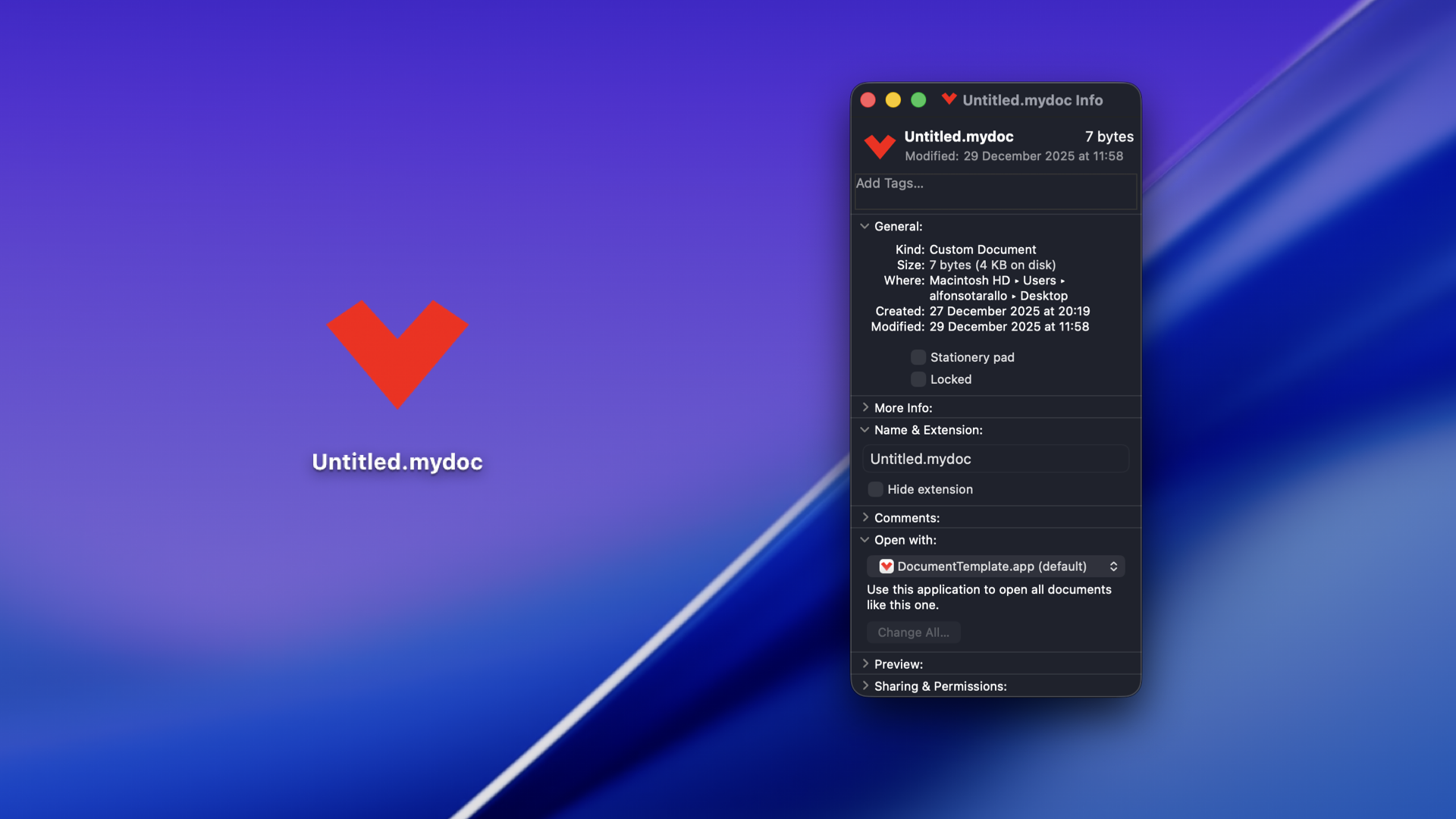

This identifier must exactly match the one declared in your app’s Info.plist. The system does not attempt to reconcile mismatches, and even small inconsistencies can prevent your app from opening its own files.

You reference these UTTypes from your document implementations to declare which formats can be read and written.

Custom Formats vs Existing File Types

Not every document-based app needs a custom file format. In many cases, supporting an existing system format is both simpler and more user-friendly. When your app works with plain text, images, or other well-known formats, you can declare support for the corresponding system UTTypes and immediately interoperate with files created by other apps.

Custom formats become appropriate when the document structure is app-specific or when you need full control over compatibility and evolution. In those cases, defining a custom UTType gives you flexibility, but it also places responsibility for versioning and migration on your app.

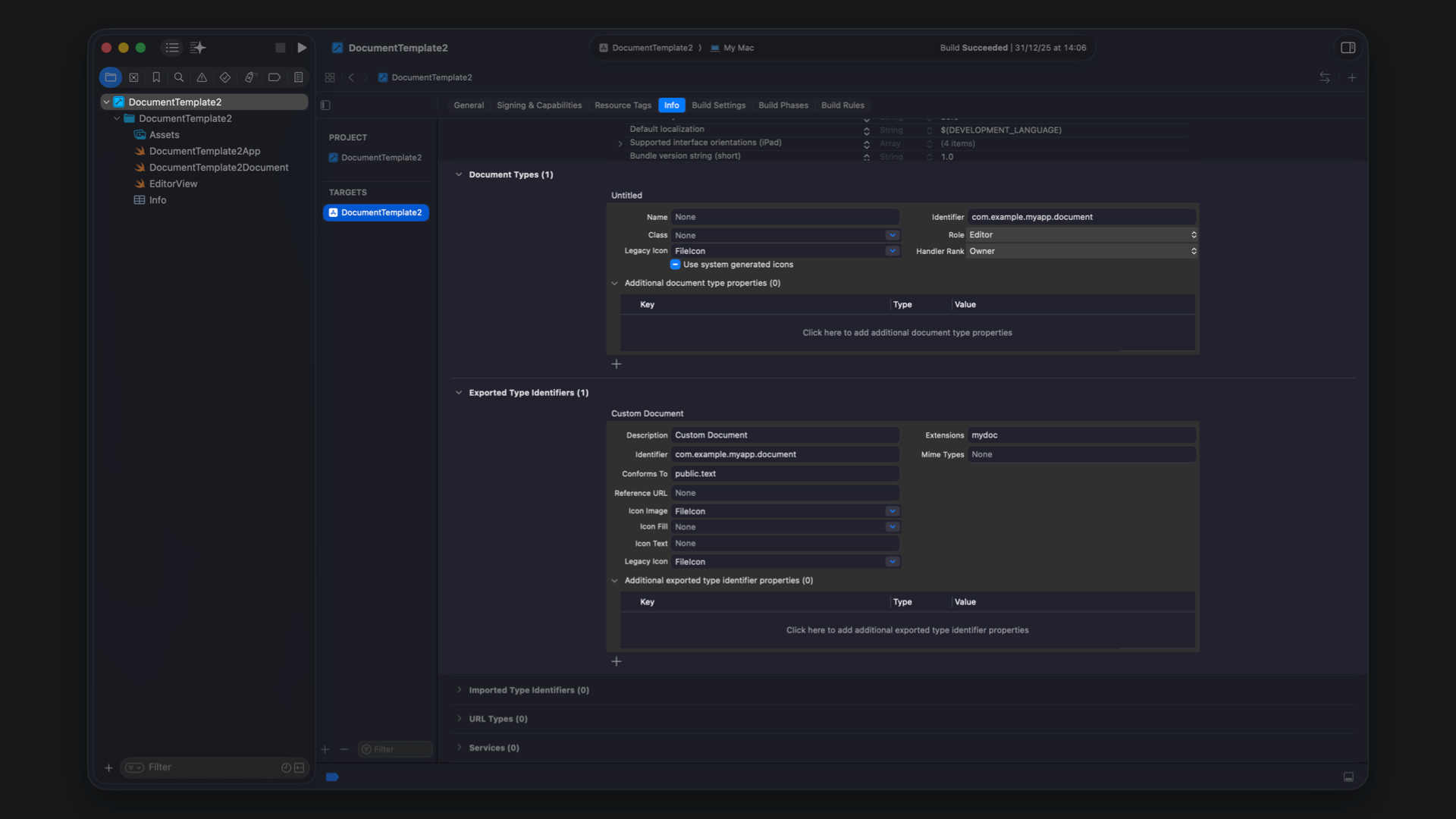

Declaring your Document Types and Type Identifiers in the Info.plist file

After defining UTTypes in code, the final step is exposing them to the system. This step is essential because SwiftUI alone is not enough: the operating system needs a declarative description of the file formats your app supports in order to route files correctly, populate document browsers, and present your app as an option in open and share system workflows.

This information lives in your app’s Info.plist. Unlike SwiftUI declarations, these entries are read by the system before your app launches and form a contract between your app and the rest of the platform. If this contract is incomplete or inconsistent with your Swift code, document-based behaviour will break in subtle but frustrating ways.

There are three distinct pieces involved: declaring Document Types (CFBundleDocumentTypes), Exported Type Identifiers (UTExportedTypeDeclarations), and Imported Type Identifiers (UTImportedTypeDeclarations). Each serves a different purpose, and understanding their roles helps avoid common configuration mistakes.

The following Info.plist example declares the custom exported document type used throughout the article, identified as com.example.myapp.document and stored using the .mydoc filename extension.

Exported Type Identifiers, UTExportedTypeDeclarations in the Info.plist file, defines file formats that your app owns. In this case, it establishes com.example.myapp.document as a first-class system type. The identifier must match the one used in Swift code, while conformance to public.text informs the system how the file should behave in generic contexts such as previews or sharing; in this case, for example, a file of this type created in your app can be opened in other apps supporting text files.

Imported Type Identifiers, UTImportedTypeDeclarations in the Info.plist file, serves a different role. It allows your app to declare support for formats defined elsewhere without claiming ownership. This is most useful for third-party or legacy formats that are not already represented by system UTTypes. Exporting a format signals ownership, while importing signals compatibility, and confusing the two can lead to incorrect app selection and unpredictable behaviour.

Document Types, CFBundleDocumentTypes in the Info.plist file, ties everything together. It declares which document types your app can open and how prominently it should appear as a handler. The handler rank influences whether your app is suggested as a default editor or merely one option among many.

When UTTypes in code and document declarations in the Info.plist align precisely, files open where users expect, your app appears consistently across the system, and SwiftUI’s document infrastructure can do its work with minimal additional logic.

Document-based apps work best when they lean into system conventions rather than fighting them. Let the system manage file creation and saving instead of introducing custom save buttons. Bind views directly to document properties so changes propagate naturally. Handle read and write errors explicitly and test document workflows on every platform you support, especially window and scene behaviour.

Keeping document models focused and well-scoped pays off over time, particularly as formats evolve.

SwiftUI’s document-based architecture is powerful, concise, and deeply integrated with Apple platforms. By combining a DocumentGroup scene, a thoughtfully designed document model, and well-defined Uniform Type Identifiers, you can build apps that respect user file ownership and scale naturally across platforms.

For developers building editors, creative tools, or file-centric utilities, understanding this model is foundational. Once embraced, the system takes on far more responsibility than most custom solutions ever could.