Designing with people: Creating applications for reality

Understand the value of designing applications, including the communities they are for, in the process.

Many apps look beautiful and polished, but quietly fade away shortly after launch. The problem isn’t always bad code or clunky design; it’s often that apps are built for individuals, ignoring the communities, networks, and relationships that shape their users’ everyday lives.

This is where co-design comes in. Co-design is not just a methodology; it's a way of designing with people and not just for them. It's about creating products through a participatory process, so that the outcome is as tailored as possible to the real needs of the community.

Adopting a co-design approach flips the perspective. Instead of asking:

“How do I solve this person’s problem?”

We ask:

“How can we improve the experience for an entire community and with the community?”

This shift may feel subtle, but it changes everything about the way we design.

Shared Language, Shared Solutions

Designing for a community requires letting go of assumptions; it starts by acknowledging that we don't know everything. The problems you imagine solving are often not the problems the community is actually struggling with. Every community is shaped by nuances that you can only discover through listening, observing, and being open to unexpected challenges.

To design for a specific community means engaging with its dynamics and its unique language. Approaching it from the outside, without truly stepping in, almost always leads to outcomes that fail to reflect real needs.

There are three concrete examples of products created for specific communities and, most importantly, with those communities.

We develop our products with’ and not ‘for’ our community. Our North Star is to serve the needs of that community as we discover them together – even if it means disrupting our assumptions, thinking, and business model.”

-Be my eyes

Be my eyes

connects blind and low-vision users with real-time visual assistance from volunteers around the world. It’s succeds not only because it's free and easy to use, but because it adopts the most friendly language ever, human touch. Engaging users by making them able to rely on volunteers that are willing to help even with the smallest issue.

Anne

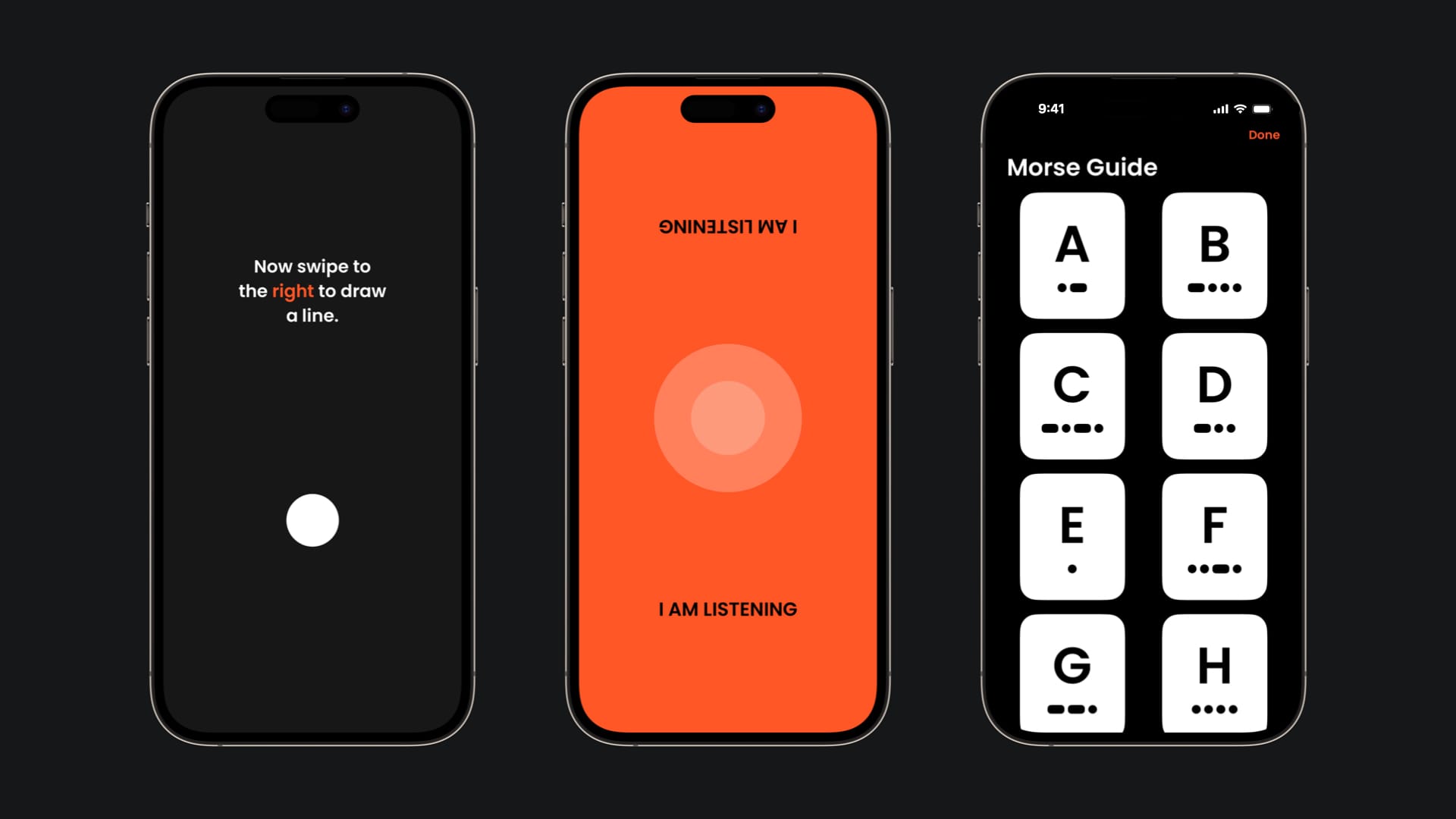

An accessibility app for deaf-blind users. Its goal wasn’t simply to make buttons bigger or add different cues, common assumptions about accessibility. Instead, Anne became a shared language: gestures, vibrations, and Morse-code patterns that work across the user’s network of caregivers, friends, and public services. Interfaces were no longer isolated screens; they were communication tools embedded in relationships. The team didn't guess these solutions, they co-created them with the community, testing, observing, and immersing themselves in the context.

Tiimo

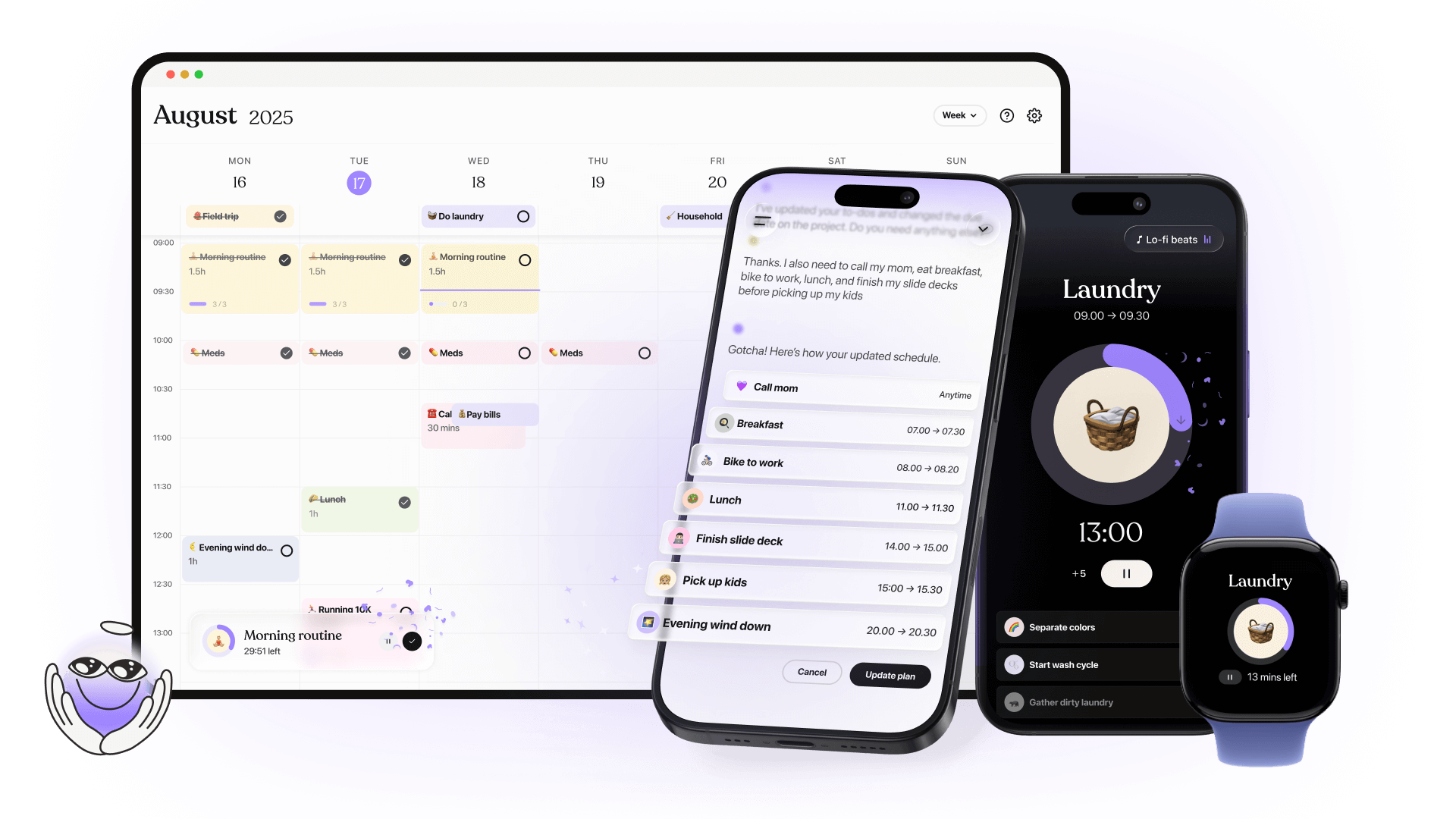

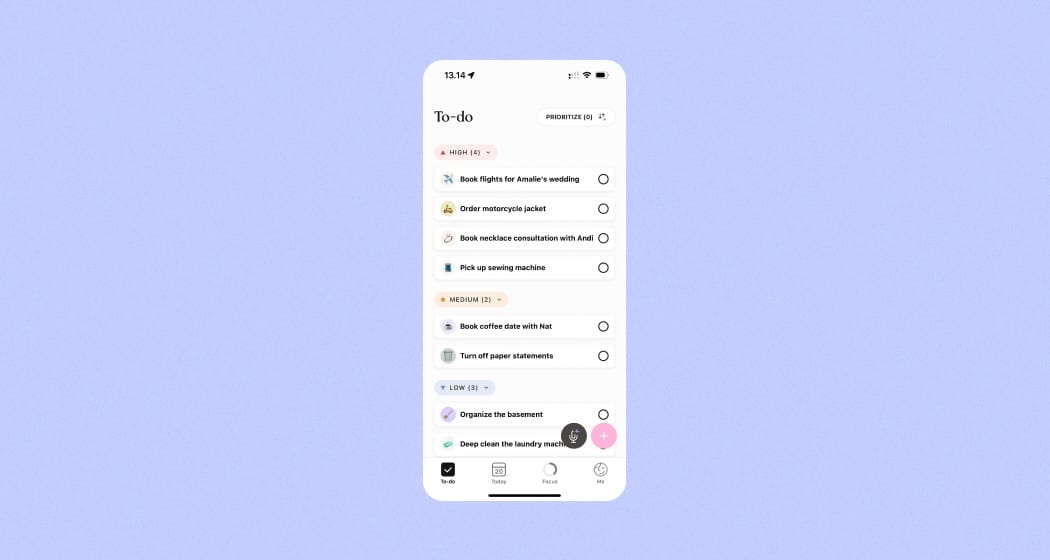

A planning app for neurodivergent users. Planning doesn’t start with a neat calendar; it starts with mental clutter, uncertainty, and unpredictable energy. Tiimo doesn’t “dictate” executive functioning; it helps users take the first step when everything feels overwhelming, bridging the moment from feeling stuck to taking action.

All these projects reveal a core lesson: assumptions about users are often wrong:

- For Be My Eyes and Anne, accessibility isn’t about enlarging visuals—it’s about using existing sensory channels and skills.

- For Tiimo, productivity isn’t about motivation or efficiency—it’s about supporting users during cognitive freezes, gently guiding scattered thoughts into actionable steps.

The design process for every meaningful product starts with listening and observing. With Tiimo, this meant returning to years of user stories: people opening the app full of hope, confronting a blank screen, and freezing under overwhelm. Designers didn’t try to force a “flow state”; they designed for the pause before action.

Similarly, Anne’s team learned that gestures, vibration patterns, and Morse code could create functional independence, rather than just adapting existing interfaces for accessibility.

Visual elements and wording

Words and icons are not decoration; they should frame and reflect the identity of the community. They need to be integrated with the community’s own guidelines and cultural context. Through the process of co-design, it’s essential to consider the language a community already uses, rather than forcing a “standard” one.

The same applies to images and symbols: they are never truly universal. Representation always depends on context. This means that developers must adapt their way of communicating, paying close attention to representation, shared language, and the symbols that carry meaning within a community.

Tiimo illustrates this beautifully: soft color-coding reduces cognitive load, timelines highlight current tasks while greying out completed ones, and icons visually organize priorities without overwhelming users. Every visual choice supports clarity, calm focus, and diverse sensory needs, demonstrating how language, symbols, and color can be a bridge to usability and belonging.

Key Principles

When applying co-design to your product, you can think of the process in five main phases:

Engage

Begin by defining the focus group you want to work with, the people whose perspectives will shape the direction of your product. Take time to clarify the outcomes you hope to achieve through conversation, and enter these interactions with openness and curiosity. Listening actively is essential. Create an environment that is inclusive and safe, where every participant feels their voice matters. Be clear about your goals from the outset, as tone and guidance set the stage for trust, honesty, and genuine collaboration.

Gather

Once engagement begins, shift into gathering insights. Organize the information you collect without forcing your own priorities onto it. Allow participants to step into the role of experts, because of the context of their lived experiences, they are. Approach this phase with humility; listen first, design second. Assume that many of your preconceptions will need to be challenged.

At the same time, broaden your lens to map not only the user, but also the network of people, systems, and contexts surrounding them. Use workshops, group activities, or creative exercises that match participants' natural ways of interacting. Be ready to adapt these frameworks along the way, shaping them to the community rather than expecting the community to adapt to you.

Understand

With rich insights in hand, the next step ti to carefully analyze the outcomes of engagement. Work toward identifying the true core problem, the issue that lies beneath surface-level frustrations. Map out both the obstacles that stand in the way of solutions and the opportunities waiting to be tapped. Support your findings with research and validation, ensuring they are accurate and not just assumptions. This stage is about turning raw stories and observations into a clear picture of what really needs to be addressed.

Implement

Now you can begin shaping solutions. Define responses that are directly tied to the needs uncovered in the earlier phases. Design features that adapt to users, rather than dictating how they must behave. Bring the solution into tangible form through an artifact: this could be a prototype, a mockup, or even a small pilot version. The aim is to create something real enough that participants can interact with, respond to, and critique.

Test

Finally, put your solution to the test in real-world conditions. Establish clear criteria for what success looks like, then step back and observe. Focus not only on ideal use cases but on the unpolished, unscripted moments of interaction. Allow users to explore the product freely, not getting stuck, they are moving smoothly, and when they stumble. Pay special attention to points of friction or confusion, as these often reveal the most valuable insights. Capture unexpected behaviours and use them to inform the next iteration. Testing is not the end of the process but the beginning of a continuous cycle of refinement and improvement.

In short, co-design is a collaborative and iterative methodology that places user experience and co-creation at the center. It leverages a variety of tools and techniques to foster inclusion, spark innovation, and create solutions that are truly relevant to the people involved.

Even when applied to simpler projects, if adapted to the product and community, co-design adds value by ensuring outcomes that resonate. It helps create products that speak the same language as the people they’re built for, leading to deeper adoption and real impact.

Discover more about the topics in the article at: