Creative Coding: Randomness and Noise

Understand how to introduce noise in your algorithms to create smooth variations that change across time and space.

As developer we are usually accustomed to associate coding with the process of sitting down, thinking about algorithms, and writing the code that executes them with one only goal in our mind: solving problems to make our life easier. Sometimes we automate repetitive tasks, some other times we make apps to respond to challenges we live in our lives. When we are creating those algorithms, what we do is basically transforming an input into a desired output.

However, in our previous articles, we have seen that actually this is not the only perspective we can approach it from, as for a long time now, artists have been using coding as a tool for creative expression. Creative coding, in fact, can be meant as one of the latest declinations of computational aesthetics: artists craft algorithms with an artistic intent in a process of search, tweaking them little by little while they are looking for an engaging outcome that is often unpredictable.

So far, we have explored the history of creative coding and how to start with it using Swift and SwiftUI.

And, we also discovered how to layer different techniques to actually begin our creative journey.

In this article we will focus on how to apply randomness and noise to create uncontrolled behaviors, in the pursuit of what we call the unexpected beauty.

Beauty in the constant process of search

At the heart of the creation of computational aesthetics there is the process of layering different techniques, approaches, and procedures, an orchestration of multiple procedural systems that interact in complex ways producing an engaging outcome.

During the exploration of the interactions between different procedures, each of them with their own dynamics, beauty often emerges. The most interesting outputs usually don’t come from control, but more from the continuous search within systems that evolve and interact beyond our full prediction. We say full prediction because when we combine randomness, noise within structure, we begin to compose a set of systems that is dynamic: as we iterate while using these procedures, each iteration becomes a new discovery, allowing us to uncover unexpected patterns and aesthetic expressions born from the orchestration of complexity and randomness. This process mirrors the artistic pursuit itself: finding beauty is a constant process of search, guided by curiosity and shaped by the interplay between intention and serendipity.

Canvas, Path and TimelineView

SwiftUI provides the tools to make the structure for this exploration immediate and intuitive. Within this environment, Canvas becomes the perfect space where code translates directly into visual form. It invites iteration and experimentation, encouraging us to think visually through algorithms and to treat each adjustment of parameters, each variation of noise or randomness, as part of an evolving artistic dialogue.

Canvas supports immediate mode drawing by giving us a context to draw with and its size; and the context itself provides methods for drawing, masking, applying filters, and transformations.

Canvas { context, size in

// Circle Size

let center = CGPoint(

x: size.width / 2,

y: size.height / 2

)

// Generating the Circle Path

let path = generateCirclePath(

x: center.x - radius,

y: center.y - radius,

width: radius * 2,

height: radius * 2

)

}

To draw a circle, for example, what we need to do is just to calculate where we want to draw the circle and create a path to be drawn. Then, with CGContext.stroke(_:) method we can actually draw that circle.

Canvas { context, size in

...

// Draw the Circle Path

context.stroke(

path, with: .color(strokeColor),

lineWidth: strokeWidth

)

}

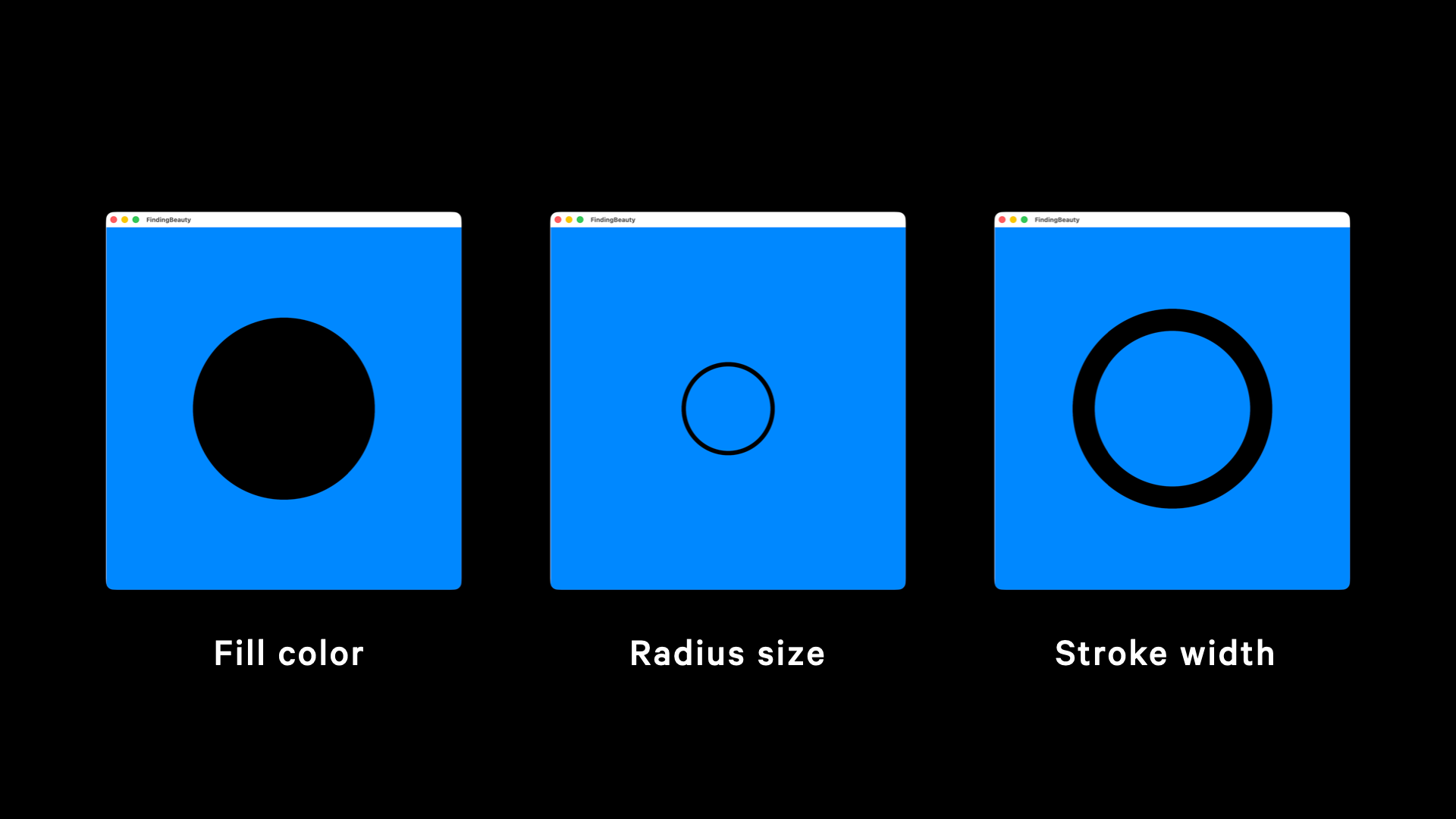

Even Path comes with different methods for defining the outlines of 2D shapes such as:

And, if we start playing around with fill color, radius size, stroke width, it’s possible to create different versions of the same shape. And these are the most basic ways to create variations.

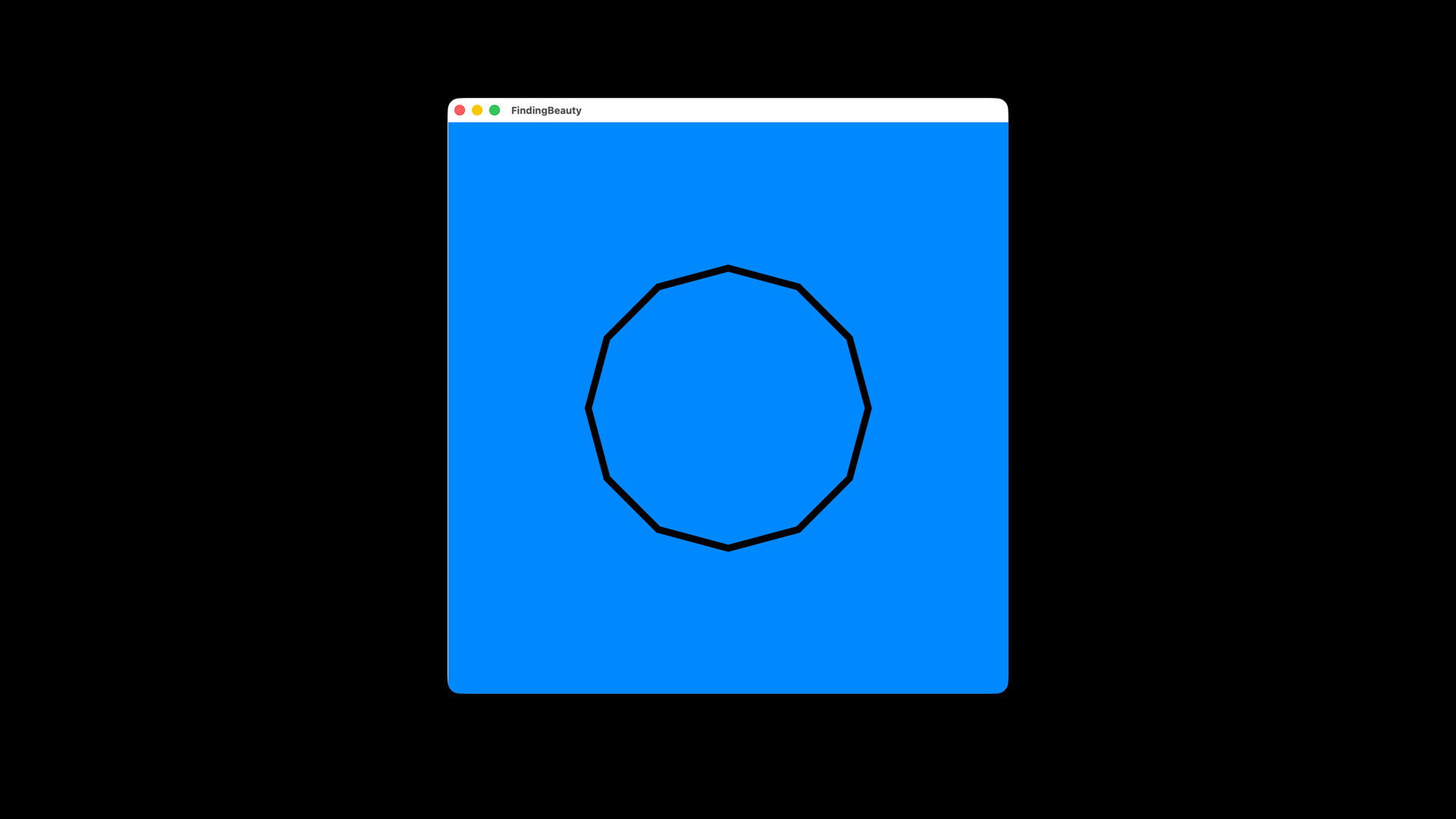

Another thing that can be explored to create differentiation is the manipulation of the points that define the shape we have just created. This approach allows us to customize a little bit more our shapes:

var points: [CGPoint] = []

// 1. Create 12 points around a circle

for i in 0..<12 {

let angle = (Double(i) / 12.0) * 2 * .pi

let x = cos(angle) * size

let y = sin(angle) * size

points.append(CGPoint(x: x, y: y))

}

// 2. Connect the points

let path = Path { path in

// 3. Move to the first point

path.move(to: points[0])

for i in 0..<points.count {

let next = points[(i + 1) % points.count]

let control = CGPoint(

x: (points[i].x + next.x) / 2.0,

y: (points[i].y + next.y) / 2.0

)

// 3. Connect the points

path.addQuadCurve(to: next, control: control)

}

// 4. Close the path

path.closeSubpath()

}

// 5. Position the circle at the center

let transform = CGAffineTransform.identity

.translatedBy(x: position.x, y: position.y)

return path.applying(transform)

For each parameter that is adjusted, such as the number of points, their distance from the center, or the formulas that determine their placement, the resulting pattern changes in ways that can be both subtle and surprising. As we are generating points through simple trigonometric relationships, we start to see how mathematical logic becomes a medium for visual exploration.

When in these complex systems time is introduced, movement becomes another tool of creative expression. TimelineView allows us to connect our drawings to the passing of time, transforming static compositions into evolving ones. Through subtle rotations, oscillations, or shifts in position, we start to perceive rhythm and flow, and we don’t even need complex formulas because these qualities emerge from simple transformations applied over time.

And, just by adding this temporal dimension, our Canvas get transformed into a living system, where code continuously generates new states, inviting us to observe and interact with the unfolding dynamics of our creation.

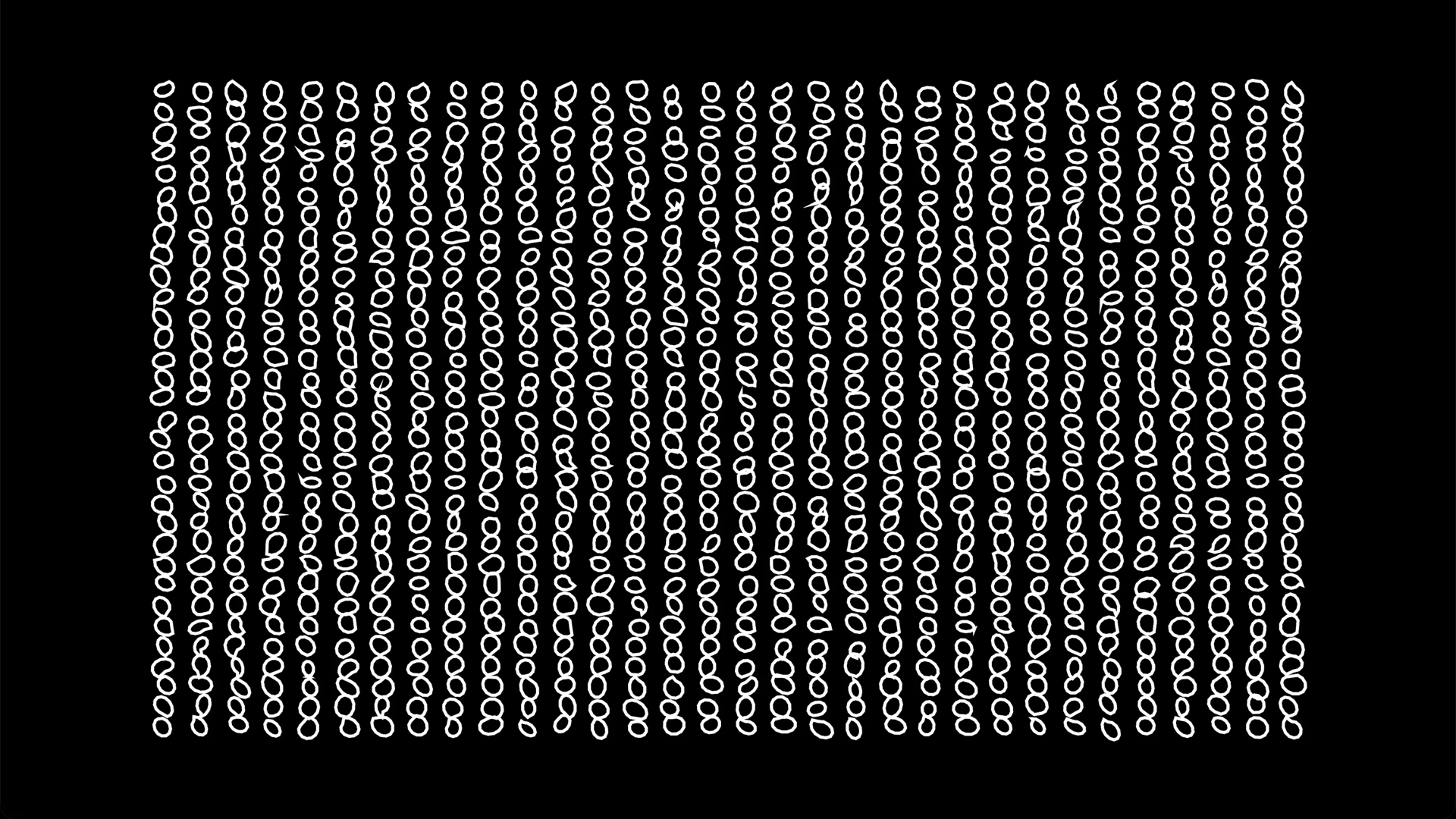

To make this living system more evident, we can create grids and/or layers of shapes that are moving all together at the same time but with different dynamics. We can begin to see emerging patterns when we draw a lot of shapes in motion with a variation to the movement of each shape: Exploring those patterns is where our search for beauty truly starts to take form.

Randomness and Noise

Things start to become very interesting when we introduce elements of randomness and noise into the properties of our drawings, opening the door to a world of unpredictability. Randomness, in fact, breaks repetition and injects variation. The differentiation that this new element introduces makes our creations behave in ways that feel organic, alive. These behaviors can be totally uncontrolled, pure chaos, or they can make patterns emerge out of it. To explore them systematically, we can define structures that help us control how randomness is applied, and that’s where our noise generators come in.

protocol NoiseGenerator {

func getValue(x: Double, y: Double, time: Double) -> Double

}

The goal of having a shared interface for our noise generators is to make experimentation modular and flexible. This abstraction allows us to swap different noise algorithms without rewriting the logic that uses them, to quote the analogy we used in our previous article, much like changing a brush in painting while keeping the same canvas. This step is very important as it gives us creative freedom to focus on how the results look and feel, rather than on the technical details of how each noise function works internally. Allowing us to define different types of noise.

Uniform Noise

Uniform noise is a type of noise generator where each value has an equal chance of being generated independently of the input values.

class UniformNoise: NoiseGenerator {

func getValue(x: Double, y: Double, time: Double) -> Double {

return Double.random(in: -1...1)

}

}

It shows the raw potential of randomness: if every value has an equal chance of appearing, this means that the final result feels energetic and unpredictable on one hand, because I cannot control which number among the range will be randomly selected; on the other hand, it is also true that sometimes it can appear too harsh or chaotic, especially when we aim for organic, natural-looking motion.

Non-Uniform Noise

If we want to soften uniform - out from pure randomness - behavior and create more nuanced visual rhythms, we can introduce bias into how our random values are selected. In fact, Non-Uniform noise is a type of noise generator where each value has a weighted implementation.

class NonUniformNoise: NoiseGenerator {

func getValue(x: Double, y: Double, time: Double) -> Double {

let random1 = Double.random(in: 0...1)

let random2 = Double.random(in: 0...1)

// Favors smaller values

// Creates a non-uniform distribution towards 0

let value = random2 < random1 ? random2 : random1

// Convert from 0...1 to -1...1

return (value * 2) - 1

}

}

This means that the balance is shifted, instead of pure randomness, we begin to guide the probability of outcomes; also, uncertainty becomes in some ways balanced, allowing to simulate behaviors that feel more lifelike and continuous. When applied to visual compositions, these irregularities can bring depth and movement, remembering the imperfections we find in natural forms.

Applying Noise to the Path

Noise can be applied directly to our geometry to distort the points that define our path, letting it subtly influence each coordinate.

var points: [CGPoint] = []

// 1. Get the source of noise

let noiseGenerator = NonUniformNoise()

// 2. Create 12 points around a circle

for i in 0..<12 {

let angle = (Double(i) / 12.0) * 2 * .pi

let baseX = cos(angle) * radius

let baseY = sin(angle) * radius

// 3. Calculate noise

let noiseX = noiseGenerator.getValue(

x: Double(i) * 0.1,

y: time,

time: time

)

// 3. Calculate noise

let noiseY = noiseGenerator.getValue(

x: Double(i) * 0.1 + 100,

y: time,

time: time

)

//4. Apply noise to distort the point

let distortedX = baseX + CGFloat(noiseX) * radius

let distortedY = baseY + CGFloat(noiseY) * radius

points.append(CGPoint(x: distortedX, y: distortedY))

}

The result is a shape that retains its overall structure but gains something new: an organic variation. In this way, the final output becomes a blend of order and randomness that reflects the essence of computational aesthetic.

This process highlights one of the most engaging aspects of creative coding: the act of tuning and observing. Small adjustments in how we calculate or apply noise can dramatically change the resulting pattern. And, if on one hand pure randomness offers infinite variation, it can also make our results unstable or inconsistent. This is the reason why more refined types of noise are important especially when we are seeking for breathing and living visual composition.

The thing about “purely random” noise is that it produces unpredictable results, which makes it hard to experiment with. Every iteration generates a completely different version of the shape, so ideally, we should work with different types of noise.

Balancing unpredictability with continuity

To gain more artistic control, we look for types of noise that are able to balance unpredictability with continuity, noise that can help us to make creations that evolve smoothly across space and time. The visual outcome that is generated is a natural flowing from the outcome of one iteration into the outcome of the following one. What we try to avoid in this context is jumping abruptly between states as we are seeking for a sense of coherence that resonates more deeply with human perception.

And, there are some types of noise algorithms that align well with our experimental goals as they don’t create obvious repetitive patterns: they provide a smooth transition between values.

Perlin, Simplex and Worley are examples of noise algorithms that you can implement as noise generators to use as the source of distortion for your shapes. Each of these algorithms produce different behaviors resulting in a different output.

By simply changing how the noise is calculated, we can see the effect on the behavior of our distortion, for example.

Perlin noise is perhaps the most iconic and used in creative coding. It produces smooth, continuous variations that transition gradually between values, creating patterns that feel organic and natural, which is actually what we are looking for in our experimentation. The difference between purely random noise and perlin one is that it generates coherence: nearby points in space or time have similar values. This capability makes it ideal for simulating natural phenomena like flowing water, drifting clouds, or gently shifting landscapes. In a creative context, it helps us to shape motion and form with a sense of rhythm and harmony, turning raw randomness into something that feels intentional, alive, and expressive.

Structured noise such as the perlin one are able to provide to our algorithms some textures because they maintain consistency across frames but at the same time they introduce some unpredictability and variation in our set of complex systems. Each algorithm brings its own aesthetic: some produce smooth, wave-like motions, others yield cellular or granular effects. Choosing between them becomes part of the creative process itself, shaping the tone, rhythm, and emotion of the final composition.

The fun really starts when we create grid visualization of multiple elements all together, all influenced by perlin noise with different seed values. What happens when we start to apply noise to the animation speed, the distortion, the color values, the stroke size and/or the size of the shape itself?

Or when we start taking advantage of the hardware capabilities of the device we are developing for?

Using the movement sensors of the iPhone to apply a change to the shapes being drawn. In the same way, you can use the microphone, the camera, and other input methods as a source of noise.

As we have seen so far, creative coding is not just about producing visuals but it’s more about exploring systems, patterns, and behaviors that emerge from the code itself. Through layering, randomness, noise, and motion, logic can become a living medium of creative expression.

Each experiment becomes part of an ongoing dialogue between control and unpredictability, structure and chance. In this constant dance between precision and imperfection, we are seeking what we call unexpected beauty, the beauty of something that surprises us in unpredictable ways.